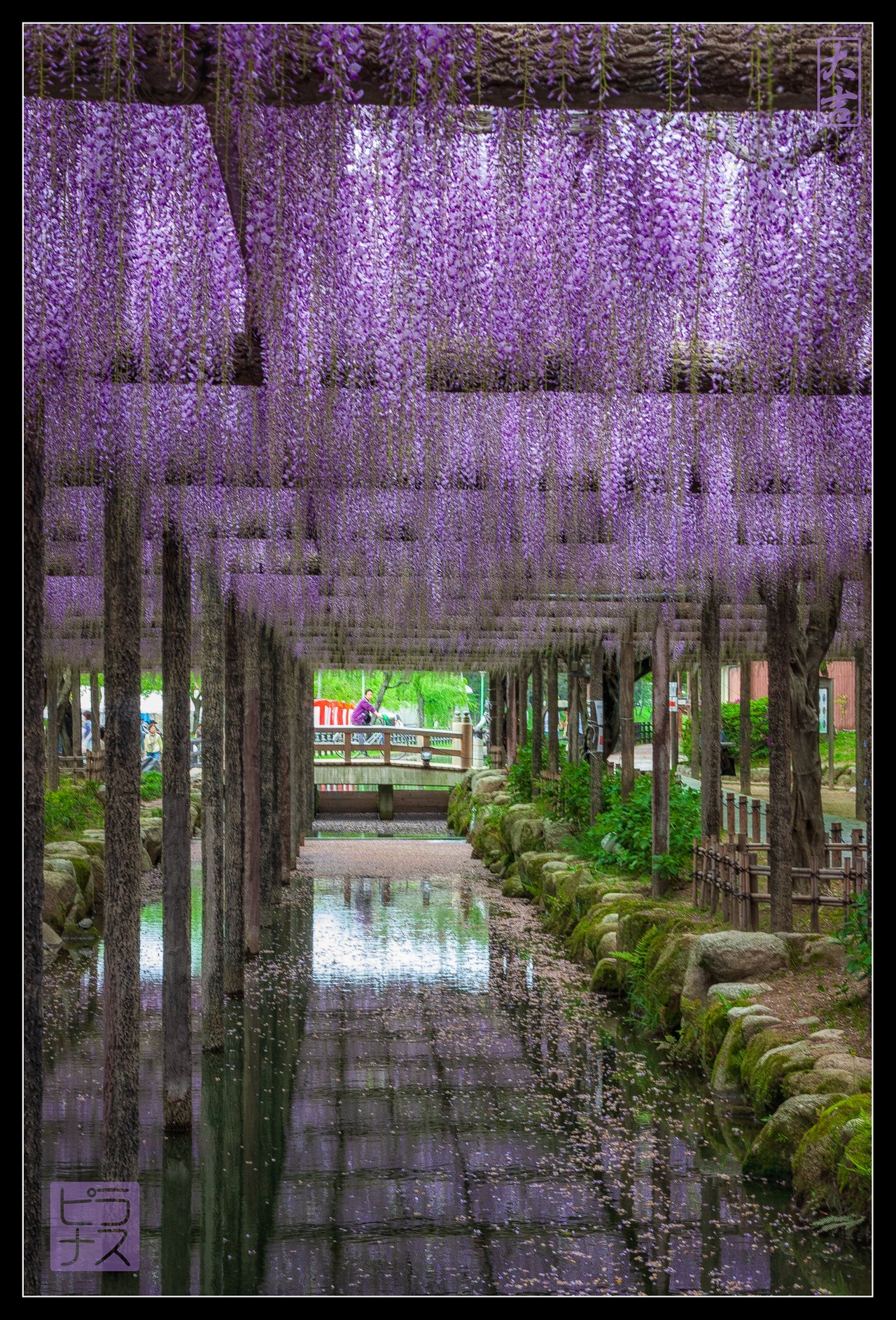

Moonlight & Wisteria ~ Haiku of Japan

The other day I posted some photos from the wisteria. Around 300 years ago, someone else was thinking of those pretty flowers. He wrote:

tsuki ni tooku oboyuru fuji no iroka kana

the scent and color of the wisteria

seem far away

—Buson

Is "wisteria" also the plural form? "Wisterias" sounds strange to me, but I could just be under the influence of Japanese here which would not change form. As you can see in the photo above and in the post I did a few days ago, the wisteria bloom in pretty big patches so I'd tend to use the word with a plural meaning.

Anyway, Buson is generally considered one of the top haiku masters in history, probably second only to Bashō. He was a painter in addition to a poet and in fact made his living primarily from his painting, at least when he was younger. Due to this, most of his haiku have an artistic quality, as if he were painting with words. This arguably makes his style more influential than the great Bashō. A hundred and fifty years later when Shiki created the modern haiku it was from Buson that he took influence, not from Bashō whom he considered overrated. And today, at least when people aren't playing simple syllable counting games, the majority of haiku people write follow this "painting with words" approach. Shiki called this shasei by the way.

There is a wonderful ambiguity in this haiku above. Is he talking of a real distance or an imagined one? If he talking of the here and now or is he wistfully thinks of the past? The wisteria already have an ephemeral quality as they only last a short time; both the setting of night and the ambiguity of the poem emphasize this. As so often with Buson, there is a sense of tranquility here, an atmosphere of contemplation. There is a strong feeling of mono no aware, which is seeking beauty and meaning in the fleeting moments of life.

The kigo (season word) here would be fuji ("wisteria"). It is a kigo for late spring.

❦

|

David LaSpina is an American photographer and translator lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time and searching for the perfect haiku. |

That is, me! If you like this translation, feel free to use it. Just credit me. Also link here if you can. ↩

I feel that there is a bit of everything in the Haiku.

Perhaps the author played with prolonged analogies about the ephemeral, displacing it into eternity. The beauty of Haiku is that it says so much with so little, not many can do it. Thank you for sharing such a beautiful Haiku.

Good day.

Yes, indeed. I completely agree.

Thanks for reading!

You’ve given me something to talk to my father-in-law about tonight.

I’m going to ask him, but maybe you can shed some light in this for me too. What does the かな way of ending a haiku mean? Is it similar to the modern use of saying かな, like adding a “I wonder” or “Perhaps” or “Maybe” to a thought?

I’m also curious about おぼゆる. Is that describing the haziness of the moon and acting like a supporting detail to the kigo, further anchoring the poem in late spring?

I tried my hand at translating this too, and have a totally different result. I wonder if I’m misunderstanding the particle usage. I once had a conversation with a literary Japanese man and he quizzed me on the meanings of sentences that were the same except for the change of one particle, and the meanings were vastly different.

I have a hard time understanding if the moon is the ficus of this poem or the wisteria.

Anyway, here’s my attempt at translating it.

The wisteria’s

color and beauty, like the

distant moon, perhaps.

-or-

The charm of the moon,

distant and hazy, like the

wisteria perhaps.

Great questions!

かな is one of the most common kireji (切れ字) used in haiku. Most traditional haiku have kireji in them. Modern haiku might not, especially if they are following one of the free-form styles, but they are still common enough.

The kireji かな, sometimes given as kanji哉 is not the same as the modern particle. It's used to add emphasis to the feeling of the poem, to give a profound feeling. Therefore it can carry a sense of awe, or doubt, or introspection, depending on the context. Also it's used to fill out mora count when one is following the traditional form and trying to get a perfect 5/7/5, which is why it's more common when writing the traditional form but less common in more modern free-style forms.

かな is usually at the end of the poem, but it can be at the end of the first or second clause, such as in this famous one from Bashō:

寒さ哉 雪を待つ程 かげろひの

There you see it is used to emphasize the feeling of cold and anticipation. It's also being used as a kind of pause for the reader to put themselves in the scene and feel it.

や is often also used in the same way, such as in basho's most famous verse:

古池や蛙飛込む水の音

As in the other one, it's being used to set the scene, to emphasize the feeling of the old pond, to invite the reader to pause and imagine it and give their mind a chance to fill in all the details of the scene that the haiku doesn't mention.

So you see it's hard to translate kireji. Different translators have different ideas. Most completely ignore them. Some like to replace them with punctuation. For example, in that Bashō's frog haiku, many replace the や with a — or ... . Others try to capture more of the feeling that they give by changing other words to show the emphasis. I don't think there is any right answer here. Each translation idea has good and bad points, so it's a balance.

For this reason one of my favorite translators and commenters, Robin Gill, used to give several translations of each haiku, attempting to highlight different aspects of the Japanese with each one and hoping that all together it would give a better idea of the feelings present in the original. I really liked his approach.

I read おぼゆる here as emphasizing the ephemeral nature of the moment. So more to add more atmosphere to the poem than anything else.

I like your ideas for translation. I'd get rid of the word "perhaps" because かな doesn't really carry that feeling here. I mean it kind of does, but in a more profound sense

I'd say the focus for this one is the wisteria. In general the kigo is always the focus. The moon is a kigo for autumn and any mention if it suggests that season, but here that is secondary to the fuji, but there is still a slight hint of that which also adds to the mono no aware feeling.

Sorry, I wrote too much. Does any of that rambling answer your question? What did you father-in-law say?

That is very interesting. I guess I never realized there was such a history to Haiku. I mean it makes sense when I think of it now, but it's one of those things you take for granted. I also think it is interesting how there were the internal feuds. Much like the great composers. Cool stuff!

Oh I could write pages of the history of haiku and internal feuds. See my reply to boxcarblue's comment to see another hint of one of those.

Part of being human, I suppose: we like to group together over shared ideas, but then immediately fall into fighting about those ideas. 🤣

Yeah, human nature always gets the best of us! I'll check out that comment!

I had an interesting talk with my father-in-law about this and about haiku in general.

He said the かな ending is often used like なぁ in modern Japanese. 綺麗だったなぁーwould be an example of how the かな ending could be used.

He also said that おぼゆるcould point to both the moon and the wisteria, which adds a level of ambiguity.

I still don’t quite understand that term, but it all added up to an interesting conversation.

Regarding the form, in my father-in-law’s study group, he said that changing the syllable count in the first and even second line is considered acceptable, but that having more than five syllables in the final line is usually frowned upon.

I don’t feel like my translation attempts are correct, but it was fun to give it a try.

Ah I just saw this reply. haha I guess I should have reloaded the page to see all replies before commenting. Anyway, I agree with what your father-in-law said.

That frowning on long syllable counts is very much a modern idea. Although they did always try to stick to the correct count back in the day—and as I mentioned in my reply above, using kireji sometimes to pad that—going over or under was not too frowned upon if it added to the poem and the poem couldn't be said otherwise. It was really only when a fellow named Kyoshi Takahama came around that that changed. He was a student of Shiki but later completely rejected all Shiki's more liberal ideas for haiku and instead insisted on a return to the traditional way. He climbed to the top of the haiku world and very very tightly controlled things. If you didn't follow his very strict sense of haiku they he would do his best to blacklist you from the industry. Seriously—he was completely ruthless.

But you know how the Japanese are, they typically try to ignore the bad when they look back at people's lives, so many books brush over some of his more draconian actions (like getting a group of anti-war haiku poets arrested during the war, where they were tortured). At any rate, it is due to his very tight control for so long that the traditional form is now seen as a requirement instead of the guideline that it was before.

I’m a bit confused by how my comments got added together here by Hive and also by drinking a few too many whiskies, but I think all thought you have said mirrors and/or supports, or is in line with what my father-in-law said, with details and focal points varying.

The night ended up being an overdrawn argument between my father-in-law an and brother-in-law about how to make more money. 🤣

At any rate, I had always assumed that かな was the equivalent of the modern particle, so the whole conversation was very enlightening for me.

It definitely makes a big difference in the way you translate a poem.

Writing haiku in English is so different. I still don’t quite know how to incorporate the bits and pieces I have learned about Japanese haiku into writing English haiku. I’m, of course, developing my own thoughts, but it’s such a peculiar art form, and making equivalent standards between the two languages is impossible.