Neutrinoless probes of neutrinos at particle colliders

In the blog of last week, I discussed neutrino physics by following a historical approach, from the early discoveries of the 20th century to today’s mysteries. These mysteries are precisely the reason that makes neutrinos interesting and appealing from a point of view of phenomena beyond the Standard Model of particle physics, and why I recently started to work on this subject.

In the present blog we take a deep dive into my own research. The post begins with a summary of the previous episode, before moving on with a description of some current probes of neutrinos. It then discusses my work, whose results have been released in two scientific publications last year (here and there). In those articles, collaborators and I proposed a new idea to get insights on neutrinos at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider. The heart of our proposal is to use processes in which two leptons (electrons, muons or taus) of the same electric charge are produced without any neutrinos.

Isn’t it cool? Looking for neutrinos without neutrinos? Large Hadron Collider’s experiments considered the idea very interesting, and now investigate data to make things concrete. Whereas their results should be out later this year, I take the opportunity today to explain how all of this works.

[Credits: Original image from KATRIN]

Neutrinos - the darkest parts of the Standard Model

Neutrinos were introduced in order to provide an explanation for intriguing results of early radioactivity studies, in the beginning of the 20th century. Energy conservation is one of the golden principles of physics. In any reaction, the energy of the initial state has to be equal to that of the final state. In beta-decay processes (in which an atomic nucleus decays into another atomic nucleus together with the emission of an electron), some energy imbalance was observed. Pauli proposed that an invisible particle carried energy away, so that the weird results only originated from our inability to detect all final-state products of the processes considered.

From that moment, a long journey started. In the Standard Model, there are three species of massless neutrinos, namely the electron neutrino, the muon neutrino and the tau neutrino. Whilst all these particles have been observed individually during the last 70 years, their properties show some intriguing issues. In particular, a neutrino of a given nature can be converted into a neutrino of a different nature when it undertakes a long-distance trip. We say it oscillates. For instance, an electron neutrino emitted at a given place in the universe can be observed as an electron neutrino, a muon neutrino or a tau neutrino on Earth, each possibility coming with a given probability.

Such a mechanism is forbidden in the Standard Model. In order to change nature during their propagation, neutrinos are indeed required to be massive particles (and not massless particles as in the Standard Model). In order to fix the theory, we consider that it includes three massive neutrinos that are admixtures of the electron neutrino, muon neutrino and tau neutrino. A given neutrino comprises thus some amount of electron neutrino, some amount of muon neutrino and some amount of tau neutrino, in addition to having mass.

[Credits: Reidar Hahn (public domain)]

The goal of current neutrino research is to measure the composition of each neutrino in terms of its electron, muon and tau neutrino ‘components’, as well as to a get precise value for its mass.

Cornering neutrino masses and properties

Neutrinos are probed in various experiments. Many of them are dedicated to measurements of the neutrino mixing parameters, and I won’t discuss them here. I focus instead on other classes of experiments.

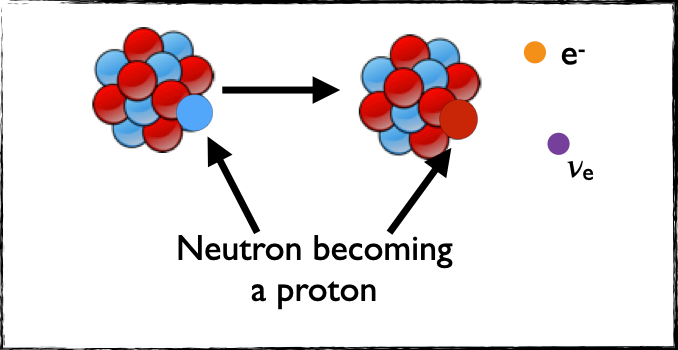

The KATRIN experiment aims to measure the neutrino mass scale from precision measurements of beta-decay processes. As already mentioned several times, in such a process a given atomic nucleus decays into another nucleus, this decay being accompanied with the emission of an electron and of an invisible neutrino.

At the level of the subatomic constituents, this consists of the decay of a neutron (blue in the image below) into a proton (red in the image below), an electron (orange in the image below) and a neutrino (purple in the image below). The difference in mass between the two nuclei gives rise to kinetic energy shared between the electron and the neutrino.

[Credits: @lemouth]

We can calculate how this energy is shared. If the neutrino is massless, then the electron can have any energy between 0 and some maximum value derived from the mass difference between the initial-state and final-state nuclei. If the neutrino is massive then this maximum energy is smaller, the exact value depending on the neutrino mass.

From a precise experimental determination of the electron energy distribution in beta decays, we can thus reconstruct the neutrino mass scale. At KATRIN, tritium nuclei (a radioactive isotope of hydrogen with two neutrons) are used. In 2019, an upper limit of 1.1 eV was set on the neutrino mass, after four weeks of operation (see here).

Is 1.1 eV a big number? In fact it is not: this is roughly one billionth of the proton mass. KATRIN still runs today and we expect to reduce the above upper bound by a factor of 5 after a data-taking period of 1000 days. This needs of course to be compared with expected neutrino masses around a few percents of an eV. We are slowly getting there…

Much better constraints come from cosmology. Neutrinos can indeed leave detectable footprints on many cosmological observables. For instance, the sum of the masses of the three neutrinos can modify the formation of large-scale structures in the universe. In order for the simulations to agree with what the universe looks like today, neutrino masses cannot be arbitrary large.

A similar conclusion can be obtained from the analysis of the cosmic microwave background (the CMB), which provides a map of how the universe was 380,000 years after the Big Bang (see here). This moment coincides with the time at which atoms were formed. Before that moment, matter was electrically charged, atomic nuclei and electrons being unbound. As a consequence, light could not travel far before interacting with something (as light interacts with electrically-charged objects).

At 380,000 years after the Big Bang light present in the universe could suddenly travel as much as it wanted (as matter in the universe was neutral). This light (i.e. the CMB) is still there today. Studying it allows us to reconstruct the properties of the early universe, which depend on the sum of the neutrino masses. Constraints can thus be obtained from a confrontation of predictions to data.

[Credits: Pierre Auger Observatory (ESA)]

Cosmologically speaking, we can also use supernovæ data, Big Bang nucleosynthesis and more. At the end of the day, we can demonstrate (see here) that the sum of the three neutrino masses has to be smaller than 0.26 eV.

In addition, another class of processes can be used to constrain neutrino properties: neutrinoless double-beta decays. Such a reaction can be seen as two beta-decays occurring simultaneously, with a subtle difference: an atomic nucleus decays into another nucleus containing two neutrons less and two protons more, together with the emission of two electrons and zero neutrino (that’s the difference).

Those processes are very important to test whether neutrinos are their own antiparticles. No observation of any neutrinoless double-beta decay has been made so far, so that constraints on models can be derived: viable theories should predict signals that fall below the sensitivity of existing experiments.

Neutrinoless double-beta processes consists of the core of what collaborators and I wanted to test in a collider study.

Neutrinoless double-beta process at colliders

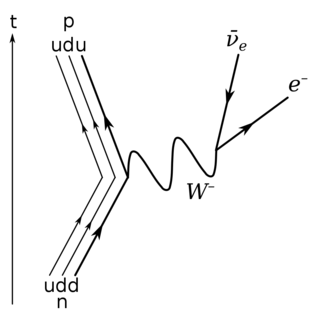

In order to understand what we did, we need to zoom a little but on how a neutron is converted into a proton, an electron and a neutrino in a beta-decay process. In terms of their quark content, a neutron is made of two down quarks and one up quark, whereas a proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark.

In a beta-decay process, one of the down quarks of the neutron is converted into an up quark, so that the neutron becomes a proton. This comes with the emission of a virtual W-boson, as weak interactions are involved. This W boson is not real as there is not enough energy compared with its mass, but we can see its manifestation through the creation of an electron and a neutrino in the final state.

To make it clearer, we can have a look at the image below in which an up quark is labelled with an u, a down quark is labelled with a d, and the proton and neutron are indicated by a p and an n respectively. The down quark of the neutron in the lower part of the figure gets converted into the up quark of the proton in the upper part of the figure, together with the creation of an electron and a neutrino (on the right).

[Credits: Hoel Holdsworth (public domain)]

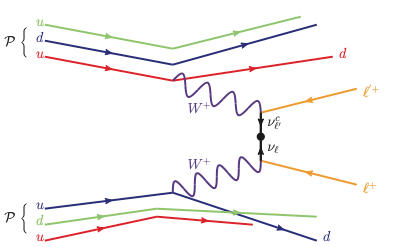

Things may now get a bit wild. I hope you will be able to follow… Otherwise, please shout at me in the comment section of this blog… In a double-beta process, a diagram as the one shown above is used twice, once as is and once tweaked.

- A first neutron decays into a proton, an electron and a neutrino. That’s the normal beta-decay process.

- The second neutron then scatters with the neutrino originating from the first decay. The final state products of this reaction are an electron and a proton. This involves the same particles as the first process (a neutron, a proton, an electron and a neutrino), but the final-state nature of the neutrino is modified into an initial-state nature.

The full double-beta process consists thus of the decay of two neutrons into two protons and two electrons. There is no final-state neutrino. Collaborators and I then had the idea to insert the double-beta decay process in a collider context. This is done by changing the final-sate/initial-state nature of the participating particles.

We considered a process in which two colliding protons give rise to two W bosons that further scatter to produce two leptons of the same electric charge. As before, there is a common neutrino exchanged between each of the ‘two branches of the process’. As one diagram is worth 1000 words, let’s have a look at the one shown below.

[Credits: Phys. Rev. D103 (2021) 114014 (CC BY 4.0)]

The two protons on the left ’emits’ each a W boson, and that the two W bosons then exchange a neutrino to produce two final-state leptons. In the shown example, both leptons have the same electric charge, that is positive. Such a signature is very rare in the Standard Model, so that the signal is quite clean.

This is called a neutrinoless process as there is no neutrino in the final state. However, investigating such a process provides access to neutrino mass and mixing parameters as there is a neutrino internally exchanged.

In our publication, we decided to focus on the case where two muons are produced, because muons are objects that can be easily detected experimentally. We thus have ideal conditions to test our idea and verify it can improve existing constraints.

We implemented a collider analysis allowing us to control the background (processes of the Standard Model giving rise to the same final state) and shown that a signal could be observed.

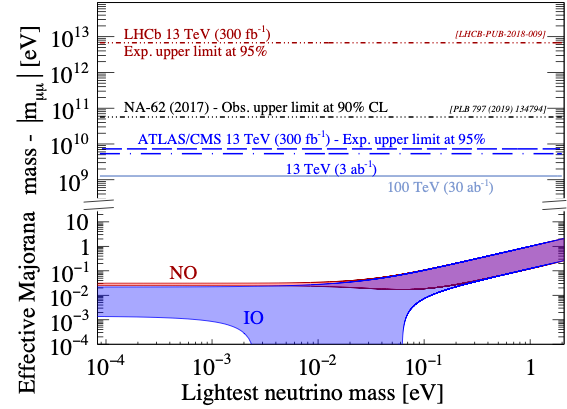

We finally converted our results into bounds on a parameter m𝝁𝝁 that incorporates neutrino masses and mixings. Our results are shown in the figure below for different possibilities for the mass of the lightest neutrino (on the x-axis).

[Credits: Phys. Rev. D103 (2021) 114014 (CC BY 4.0)]

The current constraints are given by the dot-dashed black line. Anything above this line is currently excluded by data. Our predictions for the LHC are given by the blue lines. Anything above these lines is expected to be excluded in a couple of decades, which corresponds to an improvement by a factor of 10.

We have also estimated the reach of a future 100-kilometre-long collider that would operate at an energy equal to 7 times the LHC energy. Anything above the pale blue line is reachable, which corresponds to an improvement by a factor of 100 relative to present constraints.

Unfortunately, the theory is telling us that we should find a way to improve those results by an extra factor of 10,000,000,000. Any little step in this direction is nevertheless important (so that our work is useful). We should indeed verify that no signal is indeed found for larger m𝝁𝝁 values in accordance with our understanding of neutrino phenomena.

A new way to probe neutrinos at the LHC? How does it work without reading the rest of this blog?

What is the current blog all about? In one word it is about neutrinos and my own research on that topic, which gave rise to two scientific publications in 2021 (here and there). In this post, I tried to explain what we did in those publications and why it is important.

Neutrinos are the most mysterious particles of the Standard Model. There are three neutrinos: the electron neutrino, muon neutrino, and tau neutrino. Neutrinos however mix, so that each neutrino has an electron neutrino component, a muon neutrino component and a tau neutrino component. This mixing is allowed provided neutrinos have masses, and it is up to current and future experiment to measure the neutrino mixing and mass parameters. My work fits in that context.

We proposed to use neutrinoless double-beta processes to probe neutrinos at the LHC and future colliders. In these processes, W bosons are emitted by the colliding accelerated protons. These W bosons then exchange a neutrino to produce two leptons of the same electric charge (two electrons, two positrons, two muons, one anti-muon and one positron, etc.). This reaction has the chance to be associated with a very low background, and offers thus a clean probe of physics beyond the Standard Model (and neutrino physics in particular).

In our two articles, collaborators and I demonstrated that bounds on neutrino parameters could be significantly improved at present (the LHC at CERN) and future (the FCC collider at CERN or SPPC collider in China, if approved) colliders. Our findings show that an improvement by a factor of 100 could be obtained when considering a di-muon final state.

Now, it is time to wait for the associated experimental results, that should appear later this year.

I hope you enjoyed this window on my own research. Feel free to ask any question or suggest anything in the comment section of this blog. In particular, any feedback on the clarity of the explanations is welcome. Thanks in advance!

See you next week for a special blog discussing community-based participatory research and maybe something to build on Hive and STEMsocial.

https://twitter.com/BenjaminFuks/status/1493209073147420680

https://twitter.com/A_G_Moore/status/1493458300129714182

The rewards earned on this comment will go directly to the person sharing the post on Twitter as long as they are registered with @poshtoken. Sign up at https://hiveposh.com.

if a particle is 'massless' does it have inertia?

That is an excellent question, and not a trivial one to answer.

To try to provide an answer, it is good to go back to a definition of inertia, especially as such a term is not used that much anymore. We can see inertia as the tendency for a given object to resist to a change in motion. Then, we can move one step further and definite an inertial frame of reference as a system in which the inertia of the object is equivalent to its mass. Inertia is thus somewhat a function of the object mass.

Things get more complicated when we consider speeds close to the speed of light and relativity: inertia now gets affected by the object mass and velocity (speed and direction). In other words, inertia is not anymore something intrinsic to the object. We can show (by making use of special relativity) that the object's inertia is in fact larger than or equal to the mass (we don't have a strict equality anymore).

From this last point, a massless particle can thus have inertia.

I am not 100% sure this answers fully your question, but at least it should provide seeds to discuss it further, if needed.

Cheers!

I beg your pardon... I googled those words, that seem to refer to someone who is not me.

Hello @lemouth,

The pictures alone are gorgeous (are they supposed to be gorgeous or just interesting?).

I will not comment until I have put my busy day behind me. I need to concentrate when I read this material...

11:56 PM EST, the house is quiet and I have read your blog. There is a certain pleasure in knowing that I "get" most of it, or at least the thrust of your research, I believe. Amazing.

Let me start by complimenting you on the diagram that shows a neutron becoming a proton. I actually counted the little red and blue circles. Anyone who ever solved an equation can understand why the electron and the neutrino have to share energy: because the equation has to balance. If we figure out the weight of the electron, then we can figure out the weight of the neutrino, because together their weight has to balance the equation (equal weight to the original nucleus). I'm sorry to explain what you already know, but I do think I get it and that makes me happy.

Even the neutrinoless process I sort of get. There is no neutrino at the end of the process because the boson (fuzzy concept here) exchange neutrinos so in the end we just have electrons.

Thank you, @lemouth. I don't think I have a question (unless my statement above is wrong), but I may tomorrow. There are still some fuzzy parts, but overall your conversation makes sense. It's like listening to a foreign language and missing some words but understanding the overall gist of the message.

Good luck in this amazing research. It's wonderful--a gift--that you are allowing us to witnesses this frontier-shattering adventure as it progresses.

Have a great, productive week.

Thanks once again for passing by and regularly reading my blogs!

I imagine you refer to the three pictures related to real detectors, that are indeed very beautiful (in my opinion). I have unfortunately never seen those detectors with my own eyes. The IceCube detector lies in Antarctica, so that visiting it may forever be an issue because of distance. The NOvA one is located at Fermilab, close to Chicago. I however don't know to which extent it can be seen in action. The same holds for the KATRIN detector based at KIT (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology).

For the rest, what you summarised is correct. Note that instead of talking in terms of mass, it is better to talk in terms of energy. Mass is just one form of energy, as kinetic and potential energy. What is important is that the total energy budget is conserved in any process. Then it is possible to convert some energy of a given type (e.g. mass) into some energy of another type (e.g. kinetic energy).

I am looking forward for any further questions you may have later today (which is tomorrow for you ;) ). Have a great week too!

Honestly amazing stuff. I wonder what Schrodinger would be thinking if he was reading this article. Would probably just be dumbfounded

I guess that he would be very amazed to see how the entire domain of microscopic physics has evolved during the last century. Things have moved so fast... And I do not have only in mind high-energy physics. I also think about nanosciences, quantum information, etc. The list of innovations and new developments is just enormous!

Yes it really has gotten to a stage where it is nearly impossible to keep track of even a small percentage of scientific fields. I am studying physics at the moment and I truly hope it doesn't get even more complex for the sake of the students!

Regardless of the developments, the bulk of the studies in physics won't probably (this is my opinion) be modified. The reason is that we cannot build a pyramid by starting with its top. We need first a solid basis. This basis includes classical mechanics and optics, and then we can slowly move on with more advanced subjects (electromagnetism, thermodynamics, quantum physics, etc.). Only from there we can start digging into the highest-level topics, which usually occurs only during the (end of the) master studies or PhD education.

This being said, there are possibilities to do interesting stuff even at the bachelor level. I currently have two bachelors working on their thesis, and we study together dark matter production at particle colliders. Whereas they don't have all the necessary background to understand all the details of the quantum field theory calculations inherent to their work, they manage to learn a lot (that's the most important part) and move on with the project, as many things can be done following "recipes".

Impressive. How can you wait all those long times before getting results for your researches is beyond me :p physicists' patience is under appreciated!

Sounds like a factor of 5 isn't enough? You mentioned "some can be massless" in one of our convos before, can 2 of them be massless and just 1 has the mass, or is there no clue yet?

Thanks for passing by, and the interesting comments/questions.

We have indeed a factor of 5 between the 1.1 eV and 0.26 eV bounds, but we should keep in mind that those limits are coming from independent experimental probes. What is aimed at KATRIN is to improve the 1.1 eV limit without relying on cosmology. It is always crucial to have independent checks on a given quantity (here the sum of the three light neutrino masses).

Data is not incompatible with the fact that one neutrino could be massless. For now, only two mass differences have been measured, and there is room for the lightest of the three neutrinos to have a mass compatible with zero. However, this does not allow two neutrinos to be massless.

Okay, that clears it up.

Yup, I was wondering what if data doesn't match up. Because currently it does seem far off from observations with cosmology.

If data does not match, then we will have another puzzle to add to our already-long list. I would like to think this would be an exciting situation :)

Some of the content in this blog actually answered the question I was asking the last time.

I am just here wondering when my country will develop to the extent of funding this kind of research because I can imagine the amount of funds that go into this kind of work.

I cannot really answer for Nigeria. However, the development of science in African countries is something in which many countries have interest now. This goes beyond physics (and particle physics in particular).

I personally have strong ties with U. Johannesburg, although I agree South Africa is probably different in terms of economy and political stability from the rest of the continent.

In addition, together with collaborators we will apply for funding to build a new master of science in corpuscular physics in Kinshasa in RDC. The idea here is to help (both financially and in terms of expertise) local people to build something sustainable on the long term. Why RDC and not another country? Well, few individuals do not have the strength to deploy their help everywhere, and choices (for good or bad reasons) have to be made. The reason behind the choice of Congo is related to existing links between the project investigator and this country.

It must feel cool, probing nature like this and observing what it gives you! Not that different from how children learn about their environment, but at a much higher level.

I like this comparison. Physicists behave sometimes like a bunch of kids with mind-blowing toys ;)

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

You may also include @stemsocial as a beneficiary of the rewards of this post to get a stronger support.

Your content has been voted as a part of Encouragement program. Keep up the good work!

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more

This is really interesting and educative to learn from

Thank you. I am happy to read that you have appreciated this blog. Please do not hesitate to write any question you may have about this blog, or even about (particle) physics in general.

Cheers!

Congratulations @lemouth! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s):

Your next target is to reach 76000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out the last post from @hivebuzz:

I have to read more about to completely understand what you are writing about. It is very interesting. Thanks for sharing.

If you look for more information on that precise topic, I can definitely recommend my previous post on this topic, that starts from the basics. But I must confess that I am not very objective with such a recommendation, and you can probably find very good other introduction on the web.

Thanks. I will read your mentioned post tomorrow.