Darkness: The tunnel [IT-EN]

Darkness: The tunnel [IT-EN]

Vanni era un tipo minuto, introverso, l’ultimo di nove figli, arrivato quando ormai non era più tempo per la madre di fare figli, ma ne aveva fatti tanti e uno in più non faceva differenza.

Ma Vanni non era come i suoi fratelli e le sue sorelle, non aveva quel fisico forte di chi nasceva in campagna. Ancora bambino sembrava già un contabile, un travet. I fratelli lo prendevano in giro ma le sorelle lo coccolavano e, in fondo, tutti gli volevano più bene anche per quello, per la sua fragilità, oltre che per il fatto di essere il più piccolo.

Contrariamente ai suoi fratelli Vanni dopo le elementari continuò a studiare, visto che mandarlo a lavorare nei campi sembrava impossibile, sembrava si potesse rompere da un momento all’altro, al minimo sforzo.

Finite le scuole superiori Vanni trovò lavoro nella città più vicina, famosa per la lavorazione dell’oro. La sua specialità divenne ben presto la riparazione degli orologi. Crescendo Vanni era diventato un tipo preciso, perfezionista, schivo nel carattere e lavoratore come pochi in azienda.

Arrivava dal paese al laboratorio molto presto alla mattina, si aggiustava l’oculare e cominciava a riparare preziosi orologi d’oro, incastonava a volte anche diamanti o pietre preziose, in gioielli che erano anche orologi o orologi che erano anche gioielli, dipendeva dai punti di vista.

Meticoloso e grande lavoratore era apprezzato dai proprietari ma malvisto dai colleghi, molto più attaccati allo stipendio piuttosto che al lavoro.

Vanni non si fece mai amici sul lavoro, gli altri lo salutavano e tanto bastava, se avessero potuto, si sarebbero evitati anche quella incombenza fastidiosa, ma il laboratorio era uno stanzone e i proprietari lavoravano insieme a tutti gli altri, quindi, almeno in apparenza, tutti lo rispettavano, anche se sotto sotto lo detestavano per quel suo attaccamento al lavoro e per la sua precisione così irritante.

Vanni non aveva però un grande senso artistico e non aveva estro per gioielli, incastonature di pregio e tagli particolari, si occupava degli orologi, dove precisione e dedizione erano più importanti di vanesie velleità artistiche.

Timido e restio ai rapporti umani, non fu mai favorito dalla sua aria dimessa, dalle sue poche parole strappate solo per dovere ad un silenzio compìto. Vanni conosceva solo lavoro e famiglia, raramente aveva frequentato cinema e mai balere o discoteche. Gli unici vizi che si concedeva erano una collezione di orologi usati di grande valore, che aveva messo insieme negli anni comprandoli a pochi soldi da ricchi proprietari felici di liberarsene e il fumo. Dall’età di quindici anni Vanni fumava con impazienza e rabbia fino a tre pacchetti di sigarette al giorno. Le aspirava quasi come una sfida, con accanimento, in fretta, con il cipiglio di un Humphrey Bogart contadino. Così Vanni arrivò ai quarant’anni senza mai aver conosciuto una donna, senza aver mai parlato con una donna, senza aver mai mostrato nemmeno il minimo interesse per il mondo femminile. Vanni non aveva mostrato, a dirla tutta, nessun interesse per il mondo in generale e le donne ne erano solo una manifestazione particolare, non più degne di nota di tutto quanto il resto.

Vent’anni di lavoro non avevano significato per lui aumenti di stipendio, carriera o novità di alcun tipo, la sua vita scorreva precisa come i suoi orologi dopo la sua attenta riparazione.

Non aveva mai fatto vacanze, quando era in ferie restava a casa a riparare i suoi orologi, quelli della sua collezione personale. Non aveva bisogni o desideri da soddisfare, perciò aveva messo via un bel gruzzoletto, cosa questa che faceva nel più totale disinteresse, semplicemente accumulando soldi in banca senza nemmeno curarsi di quanti fossero, si accumulavano avendo vita propria, solo perché Vanni non ne spendeva che una piccola parte.

Per via della sua fragilità fisica Vanni non aveva mai praticato nemmeno attività all’aperto, niente sport, niente passeggiate in montagna, niente nuoto.

Arrivò ai quaranta sovrappeso, con il viso tondo, pochi capelli in testa, una pancia di tutto rispetto e due gambette magre, senza muscoli.

Non era mai stato bello e non aveva mai nemmeno coltivato il desiderio di esserlo, non sentiva certo il peso delle trasformazioni sul proprio corpo, che passava dalle varie stagioni della vita cambiando, ma restando sempre uguale.

Il giorno che non si presentò al lavoro fu un evento, era estate e in passato aveva avuto solo un paio di influenze, non era mancato più di una decina di giorni in vent’anni.

Vanni aveva la febbre. Non la febbre che alza la temperatura del corpo, aveva la febbre sul labbro, gli capitava spesso, il dottore la chiamava Herpes, ma a casa sua tutti la chiamavano febbre. Tante volte l’aveva avuta e non se ne curava molto, come da sola all’improvviso arrivava, così da sola se ne andava: soltanto un fastidio.

Quella volta però una di quelle bolle era vicina all’occhio destro, quello che Vanni usava per il monocolo; senza quello non poteva fare il suo lavoro e se ne stette a casa per un paio di giorni. La febbre però non passò, anzi le bolle aumentarono, l’occhio gli faceva male, aveva problemi di visione, così Vanni decise di andare dal medico.

Il dottore lo visitò e non nascose una forte preoccupazione, gli ordinò riposo, una visita da un famoso oculista e gli prescrisse diverse medicine. Gli spiegò che l’herpes, la febbre come la chiamavano i contadini, era cosa da nulla se prendeva le labbra, ma molto difficile da curare se prendeva gli occhi.

Vanni se ne tornò a casa sconsolato e seguì alla lettera tutte le istruzioni del medico.

Il famoso oculista lo visitò dopo pochi giorni e parve ancora più preoccupato del suo medico di famiglia, gli cambiò le medicine, gli diede ricostituenti, gli prescrisse rigide norme igieniche e riposo, tanto riposo.

Dopo sei mesi di cure l’occhio destro di Vanni, disse il luminare all’ennesima visita, era compromesso per sempre, ma il vero problema era che la malattia si era trasmessa anche all’occhio sinistro e tutte le cure provate e riprovate, cambiate e ritentate non avevano dato nessun effetto.

Vanni ormai non lavorava più da mesi e non sapeva cosa fare tutto il giorno, si guardava allo specchio per controllare le condizioni dei suoi occhi.

Con il destro ormai vedeva ben poco e anche il sinistro cominciava a dargli dei problemi.

Passarono pochi mesi e Vanni aveva un occhio di vetro e vedeva ombre dall’altro. Ogni luce gli provocava fastidio e dolore all’unico occhio rimasto.

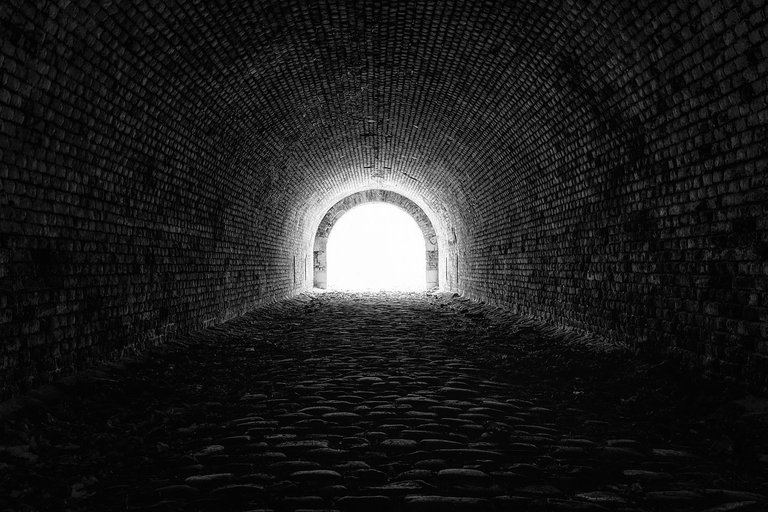

Ben presto Vanni si trovò dentro ad un tunnel: era diventato completamente cieco. Solo per non creare fastidio e repulsione nelle persone gli misero due occhi di vetro e portò occhiali scuri per nascondere anche quelli alla vista impietosa del resto del mondo.

Divenne un recluso nella casa dei genitori, ormai molto anziani, cercò di imparare l’alfabeto Braille, ma era una grande fatica che lo riempiva solo di rabbia e frustrazione.

Solo una delle sue sorelle, che non si era mai sposata e che ancora viveva coi genitori come lui, si prendeva cura di Vanni. Maria lo portava spesso in paese, gli faceva sentire il calore del sole sulla pelle, annusare la brezza della sera, ascoltare il fiume quando era grosso e rumorosamente scorreva verso valle.

Vanni non poteva più vedere i suoi orologi, poteva solo toccarli, li teneva per ore tra le mani, cercando di riconoscerli al tatto. Maria glieli prendeva dalle teche, glieli faceva toccare e quasi sempre gli diceva che ne aveva indovinato il modello. Spesso mentiva, ma non aveva cuore di ferirlo inutilmente.

Quel tunnel senza fine dove era finito lo riempiva di angoscia, non ci dormiva la notte. Certo, col tempo, aveva imparato a riconoscere delle sfumature nella voce, capiva al volo che persona aveva davanti solo sentendo pronunciare poche parole. Si divertiva a descrivere quelle persone alla sorella che all’inizio lo assecondava, come per gli orologi, poi cominciò ad averne quasi paura. La sua capacità di giudicare una persona, di tratteggiarne il carattere, le inclinazioni, di metterne a nudo l’anima in pochi secondi, sentendo, magari per sbaglio, poche parole pronunciate senza pensarci nemmeno, cominciò a metterla in soggezione. Smise anche di mentire sugli orologi, perché Vanni ormai sapeva se lei mentiva o no, leggeva dentro di lei come mai aveva saputo fare quando aveva occhi per vedere, ma nessuna voglia di capire.

Vanni comprese il suo disagio e tranquillizzò la sorella, non aveva bisogno che lei gli mentisse, piano piano avrebbe imparato a riconoscere tutti i suoi orologi, ma aveva bisogno che lei gli dicesse la verità, per affinare il tatto e giocare a quel gioco senza trucchi.

Piano piano l’umore di Vanni migliorò. Cominciò a voler uscire, Maria non dovette più costringerlo. Ora amava fare passeggiate, fumare una sigaretta con il viso rivolto verso il vento gelido, come a sfidarlo. Andavano al bar in paese a riconoscere il carattere della gente, ad indovinarne l’umore, a scoprirne le bugie, messe in bella mostra da un incespicare della lingua, da un tono di voce troppo alto, da quei mille particolare che Vanni ormai sapeva riconoscere.

Un giorno d’inverno Vanni cominciò a tossire. Tossì tutto quel giorno e poi la notte. Tossì anche il giorno seguente e Maria lo portò dal dottore.

Malgrado sciroppi e antibiotici la tosse non se ne andò e Vanni dovette fare analisi e radiografie. Aveva da poco superato i cinquant’anni e non aveva solo un tumore ai polmoni, come si sarebbe meritato con tutte quelle sigarette, così disse Maria che odiava quel suo fumare continuo. Vanni invece aveva fatto le cose in grande, gli trovarono anche molte metastasi al cervello. Mi spiace signor Vanni, purtroppo non c’è nulla da fare, non si può operare.

Lo imbottirono di farmaci, la chiamavano chemioterapia; quella cura era un po’ come scaricargli addosso tutto un caricatore, come sparargli in testa dieci pallottole, sperando che colpissero solo il male evitando il resto del cervello, difficile che funzionasse.

Infatti non funzionò.

Vanni non aveva il fisico per sopportare tutto quel vomitare, tutto quel malessere, quei già pochi capelli che gli restavano tra le sue mani incerte.

Quella difficile lotta, quel mandar giù veleno nella speranza che il male morisse prima del corpo che lo ospitava, per Vanni tutto ciò era una battaglia impossibile da vincere.

Infatti non la vinse, non giocò nemmeno a quella partita, si arrese subito.

Dei sei mesi di vita che gli diedero quando scoprirono che la sua testa era piena di macchie, ne visse solo un paio, ma li visse male, peggio di come li avrebbe vissuti se nessuno l’avesse curato, per fargliene guadagnare al massimo un paio in più, di quei mesi orribili e inutili.

Il suo tunnel era iniziato col buio che gli aveva regalato la perdita della vista.

Piano piano quel buio si era riempito di suoni, di contatti, di odori, di calore, di freddo, di equilibrio sul filo della vita, di sensazioni prima sconosciute o ignorate.

Vanni ora sta morendo, il suo respiro si è fatto affannoso e si ferma nei denti, il buio che lo aspetta è un buio definitivo, profondo, senza appello, senza fronzoli.

Vanni ora è cieco, non vede nessuna luce ad attenderlo in fondo al suo tunnel.

Vanni was a small, introverted type, the youngest of nine children, who arrived when it was no longer time for his mother to have children, but he had made many and one more made no difference.

But Vanni was not like his brothers and sisters, he did not have that strong physique of those born in the countryside. As a child he already looked like an accountant, a travet. His brothers made fun of him but his sisters cuddled him and, after all, everyone loved him more for that too, for his fragility, as well as for being the smallest.

Unlike his brothers, Vanni continued to study after elementary school, since sending him to work in the fields seemed impossible, it seemed that he could break at any moment, at the slightest effort.

After high school, Vanni found work in the nearest town, famous for its gold processing. His specialty soon became watch repair. Growing up Vanni had become a precise type, a perfectionist, shy in character and hard worker like few in the company.

He arrived from the village to the laboratory very early in the morning, adjusted his eyepiece and began to repair precious gold watches, sometimes even set diamonds or precious stones, in jewels that were also watches or watches that were also jewels, it depended on the points of sight.

Meticulous and hardworking, he was appreciated by the owners but frowned upon by his colleagues, who were much more attached to salary rather than work.

Vanni never made friends at work, the others greeted him and that was enough, if they could, even that annoying task would have been avoided, but the laboratory was a large room and the owners worked together with all the others, so, at least in appearance, everyone respected him, even if deep down they hated him for his attachment to work and his irritating precision.

Vanni, however, did not have a great artistic sense and did not have a flair for jewels, precious settings and particular cuts, he dealt with watches, where precision and dedication were more important than vanity and artistic ambitions.

Shy and reluctant to human relations, he was never favored by his modest air, by his few words torn only out of duty to complete silence. Vanni knew only work and family, he had rarely attended cinemas and never dance halls or discos. The only vices he allowed himself were a collection of high-value second-hand watches, which he had put together over the years by buying them cheaply from wealthy owners happy to get rid of them and smoke. From the age of fifteen, Vanni smoked up to three packs of cigarettes a day with impatience and anger. He aspired to them almost as a challenge, fiercely, quickly, with the frown of a farmer Humphrey Bogart. So Vanni reached the age of forty without ever having met a woman, without ever having spoken to a woman, without ever having shown even the slightest interest in the female world. Vanni hadn't shown, to be honest, any interest in the world in general and women were just a particular manifestation of it, no more noteworthy than all the rest.

Twenty years of work did not mean for him salary increases, career or news of any kind, his life flowed as precise as his watches after its careful repair.

He had never taken a vacation, when he was on vacation he stayed at home to repair his watches, those from his personal collection. He had no needs or desires to satisfy, so he had put away a nice nest egg, which he did with the utmost disinterest, simply accumulating money in the bank without even caring how many there were, they accumulated having a life of their own, just because Vanni did not spend anything but a small part.

Due to his physical frailty, Vanni had never even practiced outdoor activities, no sports, no mountain walks, no swimming.

He came to forty overweight, with a round face, little hair on his head, a respectable belly and two thin little legs, without muscles.

He had never been beautiful and he had never even cultivated the desire to be, he certainly did not feel the weight of the transformations on his body, which passed through the various seasons of life changing, but always remaining the same.

The day he didn't show up for work was an event, it was summer and in the past he had only had a couple of influences, he hadn't missed more than ten days in twenty years.

Vanni had a fever. Not the fever that raises the temperature of the body, he had a fever on his lip, it often happened to him, the doctor called it Herpes, but in his house everyone called it fever. So many times she had had it and didn't care much about it, just as it suddenly arrived by itself, so it went away by itself: just a nuisance.

The doctor examined him and did not hide a strong concern, ordered him rest, a visit to a famous ophthalmologist and prescribed various medicines. He explained to him that herpes, fever as the peasants called it, was nothing if he took his lips, but very difficult to cure if he took his eyes.

Vanni went home disconsolately and followed all the doctor's instructions to the letter.

The famous ophthalmologist visited him after a few days and seemed even more worried than his family doctor, he changed his medicines, gave him tonic, prescribed strict hygiene rules and rest, lots of rest.

After six months of treatment, Vanni's right eye, the luminary said at the umpteenth visit, was compromised forever, but the real problem was that the disease had also spread to the left eye and all the treatments tried and tested, changed and tried again they had not given any effect.

Vanni hadn't worked for months now and didn't know what to do all day, he looked in the mirror to check the condition of his eyes.

With his right hand he could see very little now and his left was also beginning to give him problems.

A few months passed and Vanni had a glass eye and saw shadows on the other. Each light caused him discomfort and pain in the only eye left.

Vanni soon found himself inside a tunnel: he had become completely blind. Just so as not to create annoyance and repulsion in people they put two glass eyes on him and he wore dark glasses to hide even those from the merciless view of the rest of the world.

He became a recluse in his parents' house, now very old, he tried to learn the Braille alphabet, but it was a great effort that only filled him with anger and frustration.

Only one of his sisters, who had never married and who still lived with his parents like him, took care of Vanni. Maria often took him to the village, made him feel the warmth of the sun on his skin, smell the evening breeze, listen to the river when it was large and noisily flowed downstream.

Vanni could no longer see his watches, he could only touch them, he held them for hours in his hands, trying to recognize them by touch. Maria took them from the display cases, made him touch them and almost always told him that she had guessed the model. Often he lied, but he didn't have the heart to hurt him unnecessarily.

That endless tunnel where he had ended filled him with anguish, he did not sleep there at night. Of course, over time, he had learned to recognize nuances in his voice, he immediately understood what person was in front of him just hearing a few words. He enjoyed describing those people to his sister who at first indulged him, as for watches, then he began to be almost afraid of them. His ability to judge a person, to outline his character, inclinations, to bare his soul in a few seconds, hearing, perhaps by mistake, a few words spoken without even thinking about it, began to put him in awe. He also stopped lying about watches, because Vanni now knew if she was lying or not, he read inside her as he had never been able to do when he had eyes to see, but no desire to understand.

Vanni understood his discomfort and reassured his sister, he did not need her to lie to him, slowly he would learn to recognize all his watches, but he needed her to tell him the truth, to refine his touch and play that game without tricks .

Gradually Vanni's mood improved. He began to want to go out, Maria no longer had to force him. Now he loved to go for walks, smoke a cigarette with his face turned towards the cold wind, as if to challenge him. They went to the bar in the village to recognize the character of the people, to guess their mood, to discover their lies, put on display by a stumble of the tongue, by a tone of voice that was too high, by those thousand details that Vanni now knew how to recognize .

One winter day Vanni began to cough. He coughed all that day and then into the night. He also coughed the next day and Maria took him to the doctor.

Despite syrups and antibiotics, the cough did not go away and Vanni had to do analyzes and x-rays. He had just passed the age of fifty and not only had lung cancer, as he deserved with all those cigarettes, so said Maria who hated his constant smoking. Vanni, on the other hand, had made it big, they also found many metastases to the brain. I'm sorry, Mr. Vanni, unfortunately there is nothing to be done, you cannot operate.

They stuffed him with drugs, they called it chemotherapy; that cure was a bit like unloading a whole magazine on him, like firing ten bullets in the head, hoping that they would hit only the evil while avoiding the rest of the brain, which was unlikely to work.

In fact it didn't work.

Vanni did not have the body to bear all that vomiting, all that discomfort, those already few hairs that remained in his uncertain hands.

That difficult struggle, that swallowing poison in the hope that the disease would die before the body that housed it, for Vanni all this was an impossible battle to win.

In fact, he didn't win it, he didn't even play that game, he immediately gave up.

Of the six months of life they gave him when they discovered that his head was full of spots, he only lived a couple of them, but he lived them badly, worse than he would have lived if no one had treated him, to make him at most earn a couple. plus, those horrible and useless months.

His tunnel had started with the darkness that had given him the loss of sight.

Gradually that darkness was filled with sounds, contacts, smells, heat, cold, balance on the edge of life, sensations previously unknown or ignored.

Vanni is now dying, his breathing has become labored and stops in his teeth, the darkness that awaits him is a definitive dark, deep, without appeal, without frills.

Vanni is now blind, he sees no light waiting for him at the end of his tunnel.

This post was shared and voted inside the discord by the curators team of discovery-it

Join our community! hive-193212

Discovery-it is also a Witness, vote for us here

Delegate to us for passive income. Check our 80% fee-back Program

Ciao, mi sono appena imbattuto nel tuo blog. Vedo che stai andando bene qui su Hive. Dovresti provare il nostro servizio Upvote, abbiamo appena aperto la registrazione. Dai un´occhiata al nostro ultimo post. Abbiamo bisogno di più membri. 😉